Act One: Pliés for Power

“Deep pliés.” That’s something that every single one of my ballet teachers has told me. From exercises at the barre to preparation for pirouettes to jumps, pliés are something you do at every single moment in class. But why deep pliés?

According to the American Ballet Theatre, plié is a bending of the knee or knees with the legs turned out, the knees open, and the weight of the body evenly distributed on both feet [1]. But what exactly makes pliés the perfect preparation step for so many different moves, and why do they have to be deep?

When we do a plié, we bend our knees, and therefore, the length of our legs contract. When we go back up, our knees straighten up again, and the length of our legs returns to what it was. This is called an oscillatory motion, which is a motion that oscillates around an equilibrium in position [2]. For the case of pliés, this motion is the up and down motion between the very top of the plie (legs fully straight) and the very end of the plié (knees half bent or fully bent depending on if you are doing a demi-plié or a grand-plié). We can define the equilibrium as the position at the very top of the plié, with the legs fully straight.

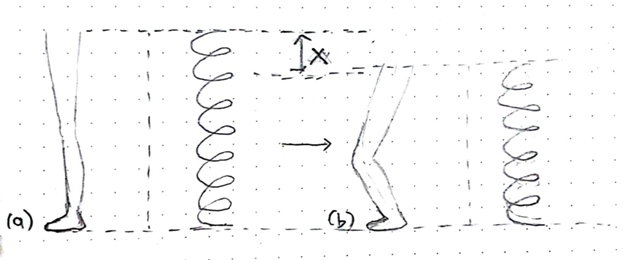

If we reduce it to its very basic components, this up and down motion can be approximated by a spring. The very top of the plié can be seen as a spring standing upright in its relaxed state, and the very end of the plié can be seen as the spring having been pressed downwards.

(a) shows the leg and spring in their relaxed states, while (b) shows the leg and spring after being pressed downwards

The reason that springs and other oscillatory motions can return to their equilibrium is because of a restoring force [2]. And because they have this restoring force, they have energy stored in them, which is called the potential energy. For an ideal spring, i.e. a massless, frictionless, and linear spring, this potential energy is

V= 1/2kx2

with V being the potential energy, k being the spring constant, and x being the displacement of the spring from its equilibrium position [3].

A linear spring means that the spring constant is constant, as the name implies. And of course, the factor of 1/2 is definitely a constant, which means the potential energy of a spring depends entirely on the displacement. Since we have that the potential energy is proportional to the square of the displacement, greater displacement means that there is more potential energy stored in the spring. In other words, the more we press down on the spring, the more energy we are going to get.

Of course, our legs are not so simple as an ideal spring. For one, our legs are definitely not massless. But using this approximation, we can see that like the spring, when we increase the difference the contraction of our legs during our pliés, aka. going deeper into them, we increase the difference in displacement from the equilibrium, and therefore we increase the potential energy stored in the plié. The bigger the potential energy in the pliés, the more energy we have to rise into our relevés, jump into our sautés, and turn into our pirouettes.

Therefore, in conclusion, the advice of deeper pliés, especially before any movement that requires power (which is all of them), is something that we all should heed. And as we go deeper and deeper into our pliés, know that piece of advice is physically accurate.

References

[1] American ballet Theater. “Learn Ballet Dictionary”. Available from: https://www.abt.org/explore/learn/ballet-dictionary/ . Accessed on December 29th, 2021.

[2] Alrasheed, Salma. 2019. “Oscillatory Motion. In: Principles of Mechanics. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation (IEREK Interdisciplinary Series for Sustainable Development)”. Springer, Cham. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-15195-9_10. Accessed on December 29th, 2021.

[3]. Morin, David. 2007. “Introduction to Classical Mechanics, With Problems and Solutions”. UK: Cambridge University Press.